The new coronavirus has reached almost every corner of the world, leaving billions in detention. The respiratory disease it causes, COVID-19, has a wide range of symptoms and a long incubation period; when most people realize they are sick, they may have been spreading the virus for days. The virus can generate paranoia almost as much as the disease – and it has left many people, including Verge’s employees anxiously looking for facts.

The media are good sources of specific growth trends and day-to-day increases, especially when there is a local context for how a region is responding. But if you want to track the pandemic’s gross mathematical progress, you may need something more specific. There are many raw data to be analyzed – tests performed, confirmed cases, hospitalizations, deaths – and each can be tracked over time or in relation to the total population. If you look at the numbers correctly, you can get a sense of how a particular region is doing when it contains an outbreak. But that requires the right graph and the right perspective on exactly what the numbers mean.

To that end, we’ve put together some of the most useful public resources – and some factors to keep in mind when you check them out.

General guidelines

As many experts have warned, even updated maps are effectively operated with a delay. Infected people can take up to 14 days to develop symptoms, and can wait even longer for a test – if they are tested. Therefore, it takes a while to see the effects of social detachment and quarantine measures.

“There is this literal data lag,” says Virginia Tech biostatistics expert Ronald Fricker The Verge. “You should always be thinking- what I’m watching today is the result of what we chose to do a few weeks ago. This is a critical piece that I think many people don’t understand.” Cases increase even after blockages start to take effect and deaths can increase well after a severe outbreak, because patients can spend weeks on treatment.

Likewise, there are many undetected cases, mainly in the United States, where the test has been catastrophically postponed. Previous research suggests that a large proportion of infected people have few or no symptoms and few countries are testing comprehensively enough to find them. But with that in mind, the sites below can clarify what we know about the spread of the new coronavirus.

The Center for Science and Systems Engineering at Johns Hopkins University (CSSE) has put together one of the simplest ways to track the virus in the world. The map aggregates data from 17 sources, including the World Health Organization, the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control and several individual governments. The website records the total number of cases by country or access point, the number of deaths and, more optimistically, the number of people who recovered.

If you want to get a general sense of the scope of the pandemic, this is a strong place to start. Note that locations classify data in several ways, which can affect the view. America’s granular reports form a huge red mass on a zoomed-out map, for example, while China also has many cases (albeit less), but has unique, cleaner looking spots for each province.

However, the case numbers do not tell the whole story. It is also useful to know how many people are being tested. In the United States, this is where the COVID Tracking Project comes in handy. The project is a voluntary effort led by Alexis Madrigal of Atlantic presenting a direct count of state-by-state tests. It collects data from known sources more reliable (especially state public health authorities), then tells you how many tests were positive or negative results, how many people are hospitalized (if these data are available) and how many died in each state.

Scattered and inadequate tests have undermined the US response, and many states are still preparing for the impact of COVID-19. Therefore, this tracker helps to transmit not only how many residents of a state are infected, but what percentage of residents are positive and how robust the testing program is. The site even assesses how states are reporting results comprehensively. “I thought this was a nice and simple way to try to get an idea of whether or not you can believe the numbers – that they totally informed them,” says Fricker.

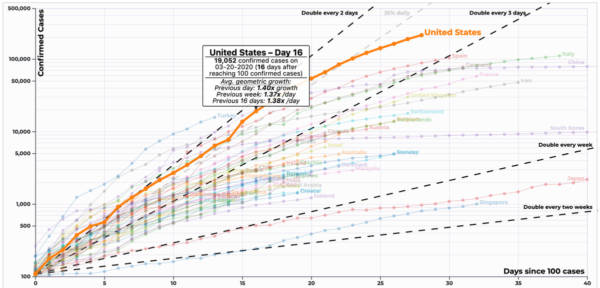

You have probably heard the phrase “flatten the curve”. Basically, if we can slow the spread of the virus long enough, we can keep infections at a manageable level so that hospitals are not overwhelmed. How do we measure this curve? Fricker recommends visualizations at 91-DIVOC, created by associate professor of computer science at the University of Illinois, Wade Fagen-Ulmschneider. The site extracts data from the Stanford panel and plots it on a graph comparing different countries or states in the U.S., with the timeline for each location starting on the day it recorded 100 cases. It marks not only the absolute growth of cases but the rate at which cases are doubling, helping readers to assess whether an outbreak is slowing down.

91-DIVOC also helps to demonstrate the value of logarithmic graphs. At the moment, a simple line graph can show an apparently exponential leap in the cases of COVID-19 – which accurately reflects how the virus is affecting people. In the meantime, logarithmic scales represent an exponential curve as a straight line, so it is easier to choose more subtle changes in the infection rate. A small slowdown can seem like cold comfort if you’re at an access point. But it is also a sign that the virus cannot be stopped – especially if companies and governments help to keep people safe and (whenever possible) at home.

Fricker also recommends country-by-country analyzes of Worldometer, a general reference site that aggregates case numbers. (It extracts data from government agencies and reliable media reports, and is one of the sources on Johns Hopkins’ map.) The Worldometer was apparently hacked in late March and some false statistics from Pakistan caused temporary panic. The numbers have been reversed, but it is a good reminder to recheck any seriously alarming trends with other panels or media.

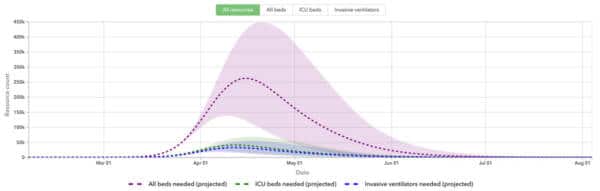

For a more concrete view of why flattening the curve is important, the University of Washington Institute of Health Metrics and Assessment (IHME) detailed how COVID-19 can affect hospitals in the U.S.

The IHME website models the growth of the virus in the coming weeks and months, projecting how many hospital beds and ventilators each state will need, compared to how many they actually have. Deborah Birx, White House coronavirus response coordinator, cited her data. The models are updated periodically, with explanations posted here.

Fricker points out that the IHME includes projection bands as colored bands, not just a single line, emphasizing that there is a lot of uncertainty in these models. He says his numbers look “a little optimistic”. For example, the website predicted about 80,000 American deaths when we talked, while estimates most commonly predict between 100,000 and 200,000 deaths. “Perhaps that is true, but I think it is the lowest point of what an epidemiologist or an expert in this field would say,” he says.

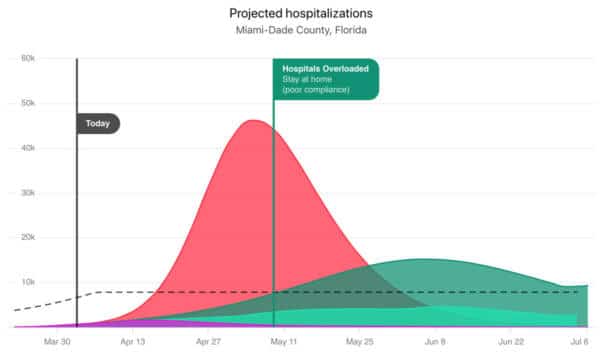

COVID Act Now presents a less optimistic model. The site was created by a team that includes former Google employee Max Henderson, Alaskan state legislator Jonathan Kreiss-Tomkins and Stanford University medical scholar Nirav Shah. It models the growth of cases in several different scenarios, including a “shelter on site” style scenario with low compliance, a well-protected order on site and a limited order of “social detachment”. The breakdown by the state also looks at what measures are being taken by the states.

The website is updated every four days and should not be a detailed forecast. Fricker believes he may also be overestimating the expansion of COVID-19, at least in the epicenter of New York. For planning purposes, however, he says it is not a bad model of what states are facing- “If you are Governor Cuomo or someone who is trying to plan this, I would err on the side of overestimation, not underestimation.”

For everyone else, it’s worth remembering that these charts need to account for feedback loops – ideally, employees will use them to decide policies such as shelter orders on the spot, which (ideally again) change the infection rate and cause the obsolete old model. Combined with the delay in detecting cases, this is yet another reason to treat models as guidelines and not as strict rules. “It is so cool that these things are being publicized, but some are very sophisticated and very complicated, and ordinary people will hardly be able to distinguish whether to believe them or not,” says Fricker.